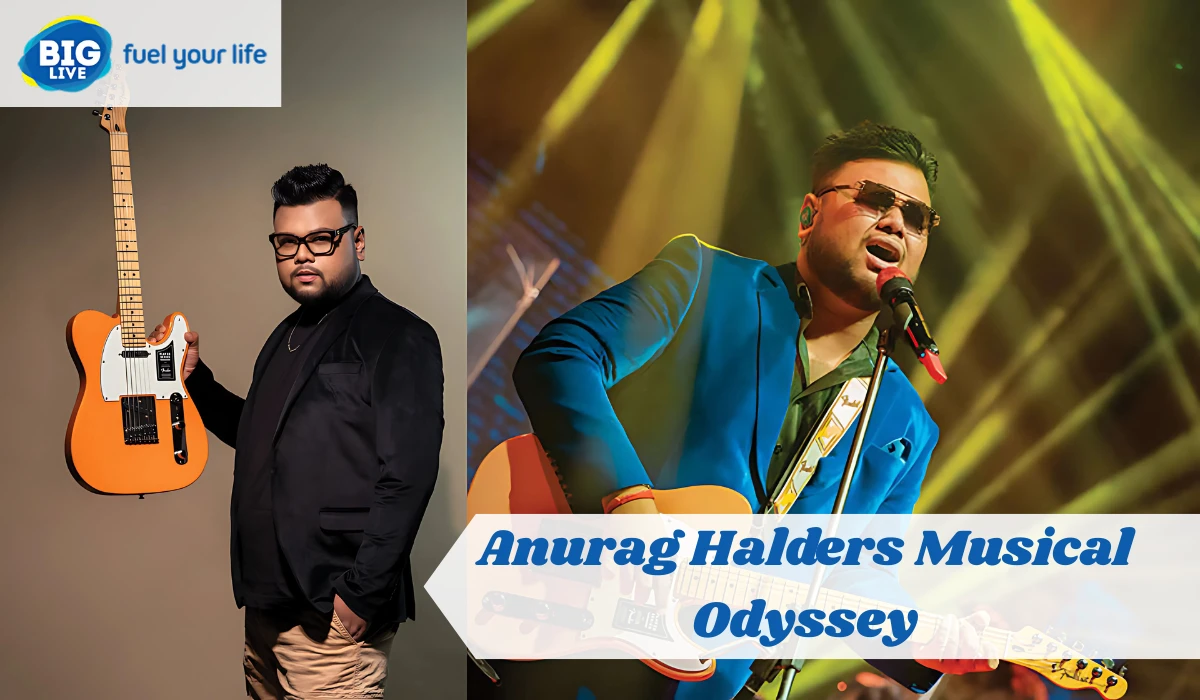

When a cracked voice floated across the Sealdah platform in early 2019, nobody stopped. Trains roared past. Porters pushed carts. The city went on. But that voice? It belonged to Anurag Halder — a boy with no home, no formal music training, and a notebook full of unshared songs. Today, his name appears quietly on Spotify playlists and under small indie music award headlines. Not everyone knows him. But those who do, don’t forget him. This is the story of a singer who never set out to be one — but became one anyway.

A Childhood on Pause

Halder was born in a crowded north Kolkata neigh bour hood. His earliest memories, he has said in interviews, include his mother stitching clothes under a flickering tube light. His father left the family early — he rarely speaks of him. They survived, barely. His mother did odd jobs. Some months were better than others. What stood out during those years, according to neighbours, was how often the child would hum film songs. “He was quiet,” one recalled, “but always singing to himself.” That would be a detail no one thought much of — until years later.

Read also: Upcoming 5 Bollywood Movies Shot in Maharashtr

The Collapse

Tragedy came without warning. His mother fell ill when he was still in his early teens. The family had no savings, no support system. She passed away before he turned 15. Left without family or shelter, Anurag drifted. First to temple grounds. Then to stairwells. Eventually, to railway stations — places where people disappeared easily. He landed at Sealdah. With a torn bag and a single pen, he spent most days avoiding attention, scribbling lyrics into a notebook when no one was looking. “I sang because I needed to hear something. Not silence,” he would later say.

Train Platforms and Tea Stalls

Between announcements and crowd rushes, Halder hummed. Sometimes it was an old Hindi tune. Sometimes, something of his own. He never asked for money. He never expected listeners. He simply sang — often seated near the chai wallahs, his back against a wall, eyes shut.

That’s how he was discovered

A student — passing through the station — stopped, pulled out a phone, and recorded him singing a self-composed melody. She posted the clip online with no caption, no hashtags. It gathered modest traction. But one viewer paused — a music producer named Rajat Ghosh, based in Dum Dum.

Finding the Voice Again

Ghosh saw the video several times. “It wasn’t the best voice,” he later admitted, “but it was the most honest one I’d heard in years.” He tracked Anurag down — a week of asking around tea vendors and platform cleaners led him to the boy himself, seated in the same spot. “I thought I was in trouble,” Anurag recalled. “No one usually talks to me.” Instead, Ghosh invited him to a recording session. It wasn’t a big studio. Just foam-padded walls and a budget microphone. But it was enough.

The First Track

The first song Halder recorded was called “Chhoti Si Raat” — a soft ballad about sleeping beneath open skies, about missing things you can’t name. There were no multiple takes. He didn’t know what those were. He sang it once. Rough, unfiltered, imperfect. But it reached people. The track was uploaded on YouTube. A few hundred views became a few thousand. Quiet, organic discovery. No influencer push. Just a song that stuck.

Small Stages, Big Echoes

Cafés in Kolkata’s Park Street area began booking him for acoustic sets. Small auditoriums offered 15-minute opening slots. He still didn’t own a phone. Borrowed one from a friend to take gig calls. His second track, “Phir Bhi Tu,” featured only a harmonium and a barely-there guitar riff. But it found its way onto Instagram reels. Quietly. It wasn’t stardom. But it was the start of stability. And for someone who’d spent two years sleeping beside suitcases and stray dogs, stability was success.

Awarded, But Not Changed

In 2022, Halder was awarded Best New Voice at the National Indie Music Awards — a ceremony meant for discovering underground talent. He arrived late. Wore an old jacket. Accepted the award, smiled once, and returned to his seat. “No speech?” the host asked.

Read also: Famous Bollywood Studios In Marathi

He replied, softly

“I used to sing to stay warm at night. I didn’t plan for this part.” The crowd applauded. A few journalists made note of the line. But Halder slipped away soon after.

A Retreat to Remember

Post-award season, Halder vanished. No social media updates. No shows. Fans assumed burnout. Some guessed label drama. The truth was quieter: he’d rented a single room near Shantiniketan with a borrowed guitar and two notebooks. Spent weeks walking. Watching birds. Writing. Out of that isolation came “Yaadon Ki Mitti” — his debut album. The songs weren’t about fame or heartbreak. They were about people who helped him survive — the old man who gave him a blanket, the tea seller who poured him a free cup after hours, a child who once offered half a biscuit.

Where He Is Now

- It’s 2025, and Anurag Halder still sings.

- He’s not on billboards. Not featured in film soundtracks. But he performs three nights a week. Travels by train. Teaches vocals at a local NGO on Sundays.

- He now rents a one-room flat. Keeps the lights low. Still writes every morning, sitting by the window.

- He says he doesn’t chase songs. “They come when they’re ready,” he says.

- He still performs “Chhoti Si Raat” at every show. Not because it’s his most popular — but because it’s the one that saved him.

The Legacy, If Any

Halder has no plans for an academy or foundation. But he’s opened a quiet music space behind a café in Dum Dum. No formal classes. Just a place where kids — many of them street-living — can sit, play, sing. He watches from a stool in the corner, humming along when needed. There’s no syllabus,” he laughs. “Just sound.”

Not a Fairy Tale

This isn’t a rags-to-riches story. It’s a rags-to-microphone one. Anurag Halder didn’t “make it big.” He made it far enough. From empty platforms to paying crowds. From humming alone to strangers singing his songs back to him. He isn’t aiming for celebrity. He just wants to be remembered by the people who need his music most. And maybe, in a world full of noise, that's enough.